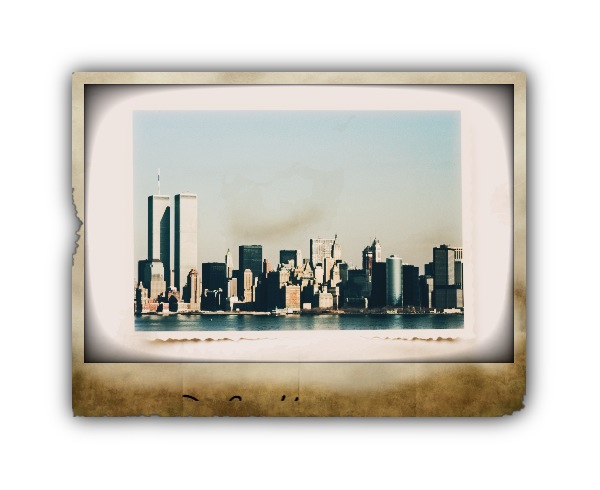

I grew up in the late 1960s, listening, over TV dinners of fried chicken and Salisbury steak, to the body counts on the news, and staring at the glow of the Empire State Building out my bedroom window every night. Green lights flooded the building on St. Patrick’s Day; red on Valentine’s Day; red, white, and blue on Memorial Day; it was shrouded in black when the city was in mourning, which was a lot in the 1960s. When it was an unrecognizable occasion, my friends and I would lay on my bed in Forest Hills, looking out the window at the pre-World Trade Center beacon of our city just seven miles away, and try to guess what the holiday was. It’s Dutch Day we once thought, when it was blue and white. One of our mothers collected Delft, and, having recently finished a class in geography, we just put two and two together.

On Halloween night in 1968, the year that the Marine captain who lived down our street didn’t come home to visit his mother, we sat in my bedroom and listened to War of the Worlds for the first time. Most of us could tell, by the dull, ancient crackle of the broadcast, that it was a hoax. But my next door neighbor, hearing the world faintly crumble around him as his parents talked about Kennedy and Chicago, and the War, and King around the dinner table every night, thought it was real: Phillip, an adenoidal, portly eight year old built a lot like Piggy from Lord of the Flies gently turned the dial on my tiny brown Zenith transistor radio until it clicked off, and staring out my window, wondered out loud if they’ll blow up the Empire State Building.

He pushed his thick plastic glasses up matter-of-factly as he lay on my Peanuts comforter, his abundant chins resting on the back of his hands.

His older brother sat up and smacked him on the back of the head.

They can’t, you idiot. This is New York City.

But at some unfathomable place deep inside us, filed somewhere between irrational childhood nightmares and a paralyzing worry about the creature under the bed, we all wondered the same thing.

I was born in Manhattan and lived in New York for 34 years; I felt safe for every one of them. I loved the city, and I never thought I’d ever leave it. I imagined the city’s place in the world along the lines of that famous Saul Steinberg New Yorker cartoon that puts it at the center of the universe, and all of its provinces (like New Jersey and Kansas) in the background. Eventually, though, I did leave, moving to Connecticut for that age-old reason that makes people do all sorts of crazy things: love. I also moved to Connecticut for a job that worked out terribly, that lasted, ironically, for nine months, and that got progressively worse and more nauseating towards the end of my third trimester. Mostly, though, I moved for Susan, and I left New York behind me in the way that a young wife, desperately in love with her new husband and wanting to begin her life, weeps for what she must leave behind in order to begin her future. But no matter where she goes or how old she gets, she will always be the child of her parents. No matter where I go, I’ll always be a New Yorker.

My leaving the city coincided with Connecticut’s snowiest winter in years. Driving back and forth, eighty miles every day from Litchfield to my office in northern Fairfield county and back again, I had sliver sharp moments of wondering whether or not I’d done the right thing, leaving my friends, my family, my home, for love. I was safe in New York, alone as I was, in my book-cramped, dark apartment in a building filled with hundreds of other similarly alone New Yorkers just like me. I wasn’t out on the roads in blinding snowstorms, or driving large distances every day on an interstate packed to capacity with maniacal, angry drivers. I walked to work in Manhattan, every day for eighteen years, and the most rattling thing I ever had to face was a crazed older man who stood on the corner of 57th and Park, howling at the morning moon about Jesus and how we were all going to hell unless we repented. Disheveled and deranged, he raged and bellowed at everyone and everything; one cold morning, I bought him a cup of coffee at the breakfast stand on the corner, and his fury was tamed.

“Have a good day sweetheart,” he’d say to me every day from that point on, until I left the city.

The most patently terrifying thing that ever happened to me was getting stuck alone in an elevator one night when I was leaving my office late; there had been a fire drill that afternoon in response to a heightened security alert a few days before, likewise in response to our publishing Newt Gingrich’s autobiography. But for some reason, I didn’t panic. I pulled out my cell phone, called my local Chinese food takeout place, and had Szechuan chicken and dumplings waiting for me in my lobby when I finally got home. The next day, sitting in my office at Harper Collins amidst manuscripts and books, looking out over the gothic spires of St Patrick’s Cathedral, I remembered that Halloween night in 1968 and our response to what we thought were Phillip’s young paranoid ravings: Nothing could ever happen here. Even after Oklahoma City, even after the World Trade Center bombing in 1993, I continued to feel safe, as most Americans, certainly, as most New Yorkers, did. I was a frequent Amtrak rider, a constant subway rider, a Long Island Railroad rider, a Greyhound bus taker, an unenthusiastic but nevertheless regular flyer, and looking back, the biggest risk I ever took in my life as a New Yorker was leaving New York.

When I left, I moved to a rural area in northern Connecticut with a population of around 3,500 mostly Polish Catholic conservatives, the kind of hardworking people who haven’t been to the city in years and don’t necessarily care if they ever see it again. I used to kid with my Connecticut co-workers, many of whom flagrantly and vehemently warned against all things remotely connected to New York, and tell them that I often felt like Woody Allen in that dinner table scene from Annie Hall, when Annie brings Alvie home to Chippewa Falls to meet his Scotch-swilling parents.

My colleagues chuckled, if a little bit carefully, like children who laugh at adult jokes that they don’t quite get.

It must be the Jewish thing, one of them actually barked at me, boldly. You’re all so paranoid.

I shuddered, and remembered my cousins, who, while living in Arkansas, told me that no one outside of New York City ever found Woody Allen movies funny, and this was finally proof positive. But I also laughed at the absurdity of the provincial stereotyping and at the fact that no one, anyone, had ever said that to me before. But really, what I had meant was that as a New Yorker, born and raised in Manhattan, I will always be looked on as being different, wherever I go. Perceived with gross suspicion as coarse malcontents who tell the truth perhaps a bit too often and perhaps a bit too directly, we are not to be trusted. We talk funny, maybe a bit too much, maybe too loudly. We wear too much black, we’re too damned smart for our own good; we have no patience, we have an edge; we have no time. We tend to be neurotic. We don’t take crap from anyone, ever. We’re not particularly well-liked, as a group. We are outsiders. Everywhere we go around the country, New Yorkers are outsiders.

On the morning of September 11th, as I unsuccessfully searched my office for a radio or a television or a computer with a sound card — the company’s infantilizing policy was to remove them so that no one could listen to music or check in with CNN during working hours — so that I could hear what was happening to my former home, I once again found myself on the outside: after trying to reach my family while simultaneously fighting off a befuddled panic at the fact that the unthinkable was happening — had happened — I raced down my office hallway, past a lineup of colleagues who, looking on stunned, watched my terror from the safe vantage point of emotional, professional, and geographical detachment. I drove back to Litchfield at eighty miles an hour, and holding Susan’s hand, watched the news, slack-jawed, in tears; at a distance of nearly 200 miles, I felt like a Venus of Wellendorf statue, with a gaping hole where my internal organs used to be, reamed away by the bitter gnash of survivor’s guilt that only a person caught between two different homes can feel.

Two days after the tragedy in New York, just as I was beginning to make it beyond page one of the newspaper every day, my company and I came to a parting of the ways, and I found myself shaken off my foundation once again. As I reeled from the terror and violence that filled the news; as more mind-numbing stories came in about last phone calls from planes and offices; as the television played the attacks over and over again and we relived them over and over again from a variety of different angles; as I realized I’d lost someone I’d recently been at a cocktail party with; as my stepbrother told us how he, at more than 240 pounds, ran down steps and steps and more steps so that he could see his family again; as it began to sink in that, no, we’re not safe in America; I found myself feeling guilty about going on with my day-to-day and the frivolities of worrying about my job when I had my life and my family had theirs and thousands of others now had neither. I had something new to grieve over and worry about, even as I realized that the creature under the bed was not only real, but horribly, palpably, sitting down to dinner with us, every night.

On Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, I didn’t want my mother anywhere near Penn Station or Port Authority, and so I drove in to New York to pick her up and bring her back to Connecticut for a dinner of brisket, roasted Fall vegetables, and the traditional apples and honey that offer the promise of a sweet New Year. As I traveled down Route 4 towards the interstate, petrified about my own reaction to the city once I saw it for the first time since the attack, I drove through one of the most conservative parts of the state. Every house, storefront, car, and bank flew an American flag. At the corner of the road, on a lawn across from the local Agway, someone had placed a sign that I last saw in the 1970s, that was as familiar a sight then as the World Trade Center: I ♥ NEW YORK.

And I realized, for the first time since I left it, that I wasn’t that far from home; in fact, I was just around the corner.

October 2001

I don’t think that no matter how you felt on September 11th and where you lived, you could relate to it in the same way a New Yorker did – even if you weren’t living in the City on that exact day. Someone said to me, “I can’t believe it’s been five months, and every time you mention that day you start to cry.” We all have our stories of where we were and what it was like. I will never forget the smell that permeated the air – and so many other things that make up my particular story. Thank you for sharing yours.

I was born and raised in New York City, moved away, and have been back for twenty-five years. When Annie Hall was in movie theaters, my husband and I were living in Atlanta. As we stood in the movie line at Lenox Square, our New Yorker friends, the Friedmans, came out of the show. Lee came up to us and said, “You will LOVE this movie – but you will probably be the only people in the theater who get it!”

She wasn’t kidding.

At the risk of stating the obvious, this one must have been difficult to write. Thank you, as always, for your very articulate, always brutally honest posts.