A Conversation with Dorie Greenspan

I first met Dorie Greenspan in 2008, when we were both speakers at the Greenbrier Food Writer’s Symposium; I knew her from her books and her reputation as the sine qua non of modern baking authors whose work included her own bestsellers like Paris Sweets and Baking: From My Home to Yours, in addition to critically-acclaimed collaborations with Julia Child, Daniel Boulud, and Pierre Herme. Renowned for her uncanny ability to marry artful precision and accessibility to tradition, warmth, and grace, Dorie can also be a quietly memorable show-stopper: one day during our Symposium, she plunked her svelte, black-clad, five foot-nothing self right down between Jeffrey Steingarten and Russ Parsons, moderated their lively and at times off-color discussion, and by afternoon’s end, had them behaving like Boy Scouts. (Even Steingarten.)

I first met Dorie Greenspan in 2008, when we were both speakers at the Greenbrier Food Writer’s Symposium; I knew her from her books and her reputation as the sine qua non of modern baking authors whose work included her own bestsellers like Paris Sweets and Baking: From My Home to Yours, in addition to critically-acclaimed collaborations with Julia Child, Daniel Boulud, and Pierre Herme. Renowned for her uncanny ability to marry artful precision and accessibility to tradition, warmth, and grace, Dorie can also be a quietly memorable show-stopper: one day during our Symposium, she plunked her svelte, black-clad, five foot-nothing self right down between Jeffrey Steingarten and Russ Parsons, moderated their lively and at times off-color discussion, and by afternoon’s end, had them behaving like Boy Scouts. (Even Steingarten.)

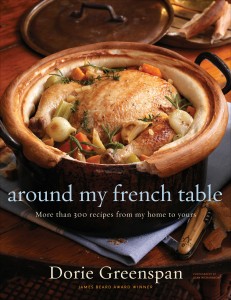

A longtime resident of New York City and Connecticut, it is Dorie’s life in Paris that has enabled her to write what is arguably one of the finest books about authentic French home cooking ever to roll off press; we can all love and respect Mastering the Art of French Cooking, but as my French friends tell me (over and over), “this is not the way the French cook at home, and it never has been.” Dorie Greenspan’s new book, Around My French Table: More than 300 Recipes from My Home to Yours (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, October, 2010) accomplishes what no other book on this most enigmatic subject has: it casts light on what the French really love to eat when they’re at home. Packed with recipes ideal for virtually every occasion, and the sort of wisdom that will make it an instant classic, Around My French Table was the subject of a conversation Dorie and I had recently…after I asked her about The Fire.

Your new book, Around My French Table, is sitting on my desk right now, already looking seriously well-used. It’s possibly the clearest interperation of French home cooking that I’ve ever read, but to start off this chat, I want to talk about something else: I want to talk about the fire. How, exactly, did you burn down your parents’ kitchen? Were they upset?

Your new book, Around My French Table, is sitting on my desk right now, already looking seriously well-used. It’s possibly the clearest interperation of French home cooking that I’ve ever read, but to start off this chat, I want to talk about something else: I want to talk about the fire. How, exactly, did you burn down your parents’ kitchen? Were they upset?

Were they upset? (laughing) So, here’s how it happened: I was in seventh grade, and I was out with my two friends Jeannie and Alan, and we were just kind of walking around, which is what you do in seventh grade. We came back to the house (in Brooklyn), and my parents were out for the evening at a formal event. We thought it would be a good idea — we had never done this before — to make a snack, and we decided to make French fries. I don’t know what got into us, because a snack would normally have been something we just opened up and ate. Anyway, we put up a pot of oil to boil.

You boiled a pot of oil?

Right. Looking back, I think we were supposed to put the fries in the oven, but we didn’t know that—we didn’t read, and we were dumb! So we put up this pot of oil, and it was taking forever to boil, so I put a cover on the pot. (Let’s keep in mind that a few years later, I took a course called Science for Poets.) Anyway, when I lifted the cover, it went up in flames. And it was gorgeous! It made this beautiful tear-shaped flame—

Dorie, you’re not a closet pyromaniac, are you?

Who knew that this would happen? I’d never seen anything like it! So we decided to put it out with a dish towel, and then we put the cover on the pot. The kitchen was filled with smoke, and the cupboards above the stove were blistered. We called the fire department, and everyone was safe and sound, but the kitchen was black and there were handprints along the ceiling from where the firemen had felt to see if anything else was hot. They sat us all out on the stoop and wouldn’t leave until my parents came home from this formal event — my father was in a tuxedo. They drove up to see the fire engines, and us sitting there. My mother said “as long as everybody is okay, that’s what matters—” I went inside to apologize to her, and she was on the floor, in her cocktail dress, crying and pounding her fists. I hadn’t cooked before that time, and I didn’t cook again.

Still, if you went to such great lengths as a child, I’m guessing that you had been bitten by the cooking bug at a very young age. You’ve also said that your mother didn’t cook; neither did mine, and I’ve always thought that I learned to cook because it was self defense. Was it a survival thing with you? When did you start to travel down the baking road?

I got married when I was 19 years old, and that’s when I learned to cook—I was excited about being married! My first apartment was with Michael, and it was like playing house! We had a tiny little kitchen, and I was just thrilled to be learning to cook, and to have friends in. I discovered that I loved it—I loved everythingabout it: the process, the sharing it, all of it. My mother was amazed that I liked it because it didn’t interest her at all. But at that time, there was no indication that it would become such a big part of my life.

When did you start to travel down the baking road?

I was always baking, because I was making dinners—whole dinners. And I was playing to an audience: everyone loves dessert! In truth, I found it very relaxing, and so it became something I did after school and after work. I did an all but dissertation for a doctorate in gerontology, and I baked my way throught it. But I also cooked, and I always say that in all those years that I was feeding people desserts, I was also giving them real food. (They didn’t get the chocolate until they ate the spinach!)

For a long time, I associated your remarkable body of work with sweets and baked goods. And most food people believe that bakers generally don’t like to cook, and cooks generally don’t like to bake: there seems to be a sort of left brain/right brain thing involved, running the gamut from precision-by-necessity to a creative adding of this and that. You seem to favor both baking and cooking.

I do think there is a different personality type that does one or the other, and they are very different, practically. In some ways, I think that baking is easier than cooking—and it’s almost controversial to say this—but if you have a good recipe in baking, you follow it. With cooking, there’s always the taste, the seasoning, is it too thick, is it too thin, is it too brown or not brown enough; with baking, you follow the recipe, you put it in the oven, there are no mid-course corrections once it goes in, and so in that way, it’s just easier. But I’ve always had “variations” in my books because I like giving people permission to make a recipe their own. And that’s also what I like about cooking. But I also find a lot of freedom in baking.

That’s interesting; I’m not a baker, but I am a cook. And since tastes change, I will make a recipe differently now than I did ten years ago, and you really can’t do that with baking. There’s also the precision factor, and when it comes to baking, precision is not my strong suit.

Well—put me in a professional pastry kitchen, and I’m very slow. When I was a professional baker, I’d finish a cake and think, “gee, if I’d only smoothed the frosting this way—”

This was at the Soho Charcuterie [in New York]?

Right. I got fired from that job for putting prunes in the cake. Remember Le Doris cake from Simca’s Cuisine—it was chocolate with almonds and whiskey-soaked raisins? That was the restaurant’s signature cake, and I replaced the raisins with prunes. And the whiskey with Armagnac. I just got bored doing the same thing the same way. Fired. Fired! I then went to work for Sarabeth Levine (at Sarabeth’s Kitchen), and I left before they could fire me. I just didn’t like doing the same thing over and over again. So if we hold with the differences between bakers and cooks, maybe there was a cook inside of me all along!

You live in New York, Paris, and Connecticut; do you find the way you cook – and think about cooking – changes depending upon where you are?

That’s intersesting—I’m in New York less than I’ve been in years, and I cook less here. But why? Maybe it’s the kitchen. I catered from this kitchen and did a million books here; I still love it, but it’s not as comfortable any longer, because I’ve been spoiled by space. I love cooking and baking in Connecticut because I have a bigger oven –- but I don’t have doubles. In New York, when I bake cookies, I have cooling racks in every room. In Connecticut, I have a dining room table, and there’s outdoor space, so I can cool pies outside, and stick stews in the snow. I’ll be working at my desk which is also in my kitchen in Connecticut, and I’ll say to Michael “there’s something that I want to try—“ and then I’ll realize that I couldn’t have done that recipe in New York. My first kitchen in Paris was teensy; I had to wash the dishes in the bathtub. It was a half kitchen—a tiny hallway between the living room and the hallway. I didn’t have an oven, but I had a half refrigerator, and I cooked up a storm there. And in this new kitchen, I have a lot of space, and I work on the island. Of course, the nice thing in New York is that if I’ve forgotten something, I can walk one block to Broadway. In Connecticut, it’s twenty minutes each way. In Paris, the shopping is the best, but it’s hard to just run out for something because the cheese is in one store, the fruit is in another, and the meat is in a third.

Let’s talk about France, the French way of cooking at home, and your new book. In America, we often tend to lump all French cooking together; this is a generalization, but it seems that we honestly believe that if it’s not from Escoffier or Mastering the Art, then it’s not accurate. Of course, those books reflected their times as opposed to our times. They were meant to teach readers how to effectively create classic cuisine as opposed to the simpler dishes that have come out of French home kitchens for years, and that keep evolving as the French population changes. In Around My French Table, you have thrown open the window onto French home cooking, in a way that no one else really ever has. It’s fun; it’s a little bit cheeky and unconventional and traditional all at once. And it casts bright light on all of those delicious Parisian home dishes that we love, but somehow can’t ever replicate. When did you know it was time to write this book? It’s like the French thing about tying a scarf: they make it look easy but they never tell you how! You tell us how—

I love France—and I’ve been dancing around writing about France. The books I did with Pierre [Herme]and Daniel [Boulud] were about their France, and I’ve written some for Bon Appetit about France as well. My husband and The Kid [Joshua Greenspan] always said “you should write about France-“ but I didn’t know how, or what. I also felt there was so much already written about it. It’s the question that anyone who writes a cookbook asks themselves: “Do I have anything different or new to say that hasn’t been said.” I proposed it just wanting to talk about the country, the food, the people I loved so much. It was on my mind all the time, and it was also my chance to spend more time there, even if I was in my kitchen in Connecticut or New York.

But I also felt like Baking [from My Home to Yours] was a kitchen journal; in many ways, this is the companion volume. It’s totally different from Baking, but it’s the other piece of my life. I look at the two books together and I think, “Okay, that’s my culinary autobiography.”

One of the things that I really love about this book is that you share myths and secrets surrounding French food and culture. I think of French home cooking as being fairly enigmatic; Americans tend to believe that it’s hugely complicated, slightly mysterious, that it takes hours and hours, that it’s enormously fancy, and that there’s some sort of inborn secret to it (the exact same secret to tying a scarf or wearing a burlap sack and having it look like Chanel). What are some of the myths and secrets surrounding French home cooking that maybe your French friends would rather you not share…?

Well, it’s like Americans and pie crust: they’re mythic—there’s this idea that you can’t make them if you didn’t learn how at your grandmother’s elbow. There is the story I tell in the book about the chocolate mousse: My friend Martine made this wonderful chocolate mousse, and it was just fabulous. I asked her for the recipe and she said “yes yes, of course,” — she’s always so generous, she always tells me when I ask where did you buy this or that. So time went by, and she never gave me the recipe. More time passed. And still no recipe. It was so unlike her! And so we were having a family meal one evening—Martine and her husband, who we’ve known for years; their cousin Anne, who introduced us to Martine, and it’s just the five of us at dinner. And as we’re leaving, Martine says “I have something for you.” And she hands me two bars of Nestle’s Dessert Chocolate. I said (suspiciously), “oh. Thank you.” She turns them over, and there is the recipe for the chocolate mousse. I told a Parisian friend of mine and she said “well of course—that’s the recipe thateveryone uses!” Another time, I went to someone’s home for dinner—she’s really not a good cook– and she made a quiche that was just out of this world, and the crust was just perfect. I was amazed by it. I kept complimenting her on it, and she kept saying “oh, thank you.” It was not until I had an apartment in Paris and could shop that I discovered that you could get perfectly rolled, all butter crust, sized perfectly, that you can just plunk down into your tart pan. That’s how she did it. But she wouldn’t tell me. I wish we had those crusts!

There’s this mythic perception that grandma is in the kitchen up to her elbows in onions or grated carrots-

And grandma CAN still be there, and so can my 26 year old friend Alice—she and her friends could be there all weekend cooking away. But on a Tuesday night when they want to have friends in, they don’t want to order in pizza, or put up a pot of pasta. There’s a recipe in the book for chicken breasts with crème fraiche and speculoos—we were having tea and she said “oh I made this great dinner for friends last night; it was so much fun—I crumbled up the cookies…” and I thought, “that to me is real French home cooking. She’s 26 years old, she loves cooking, she loves entertaining her friends, they eat at one another’s homes, they love cooking for one another, and they do quick, easy things, but with style. To me, this is what’s exciting about what’s happening, and the traditional food is still there. I did a dinner party and served hachis parmentier –- really a meal of leftovers for the family –- but I served it to Pierre Herme and others. People were so happy; it was so hot that I said “be careful!” and Pierre said “that’s always true about hachis parmentier!” But I served it to French people—and they loved it! They knew it from childhood. So it’s this mix of tradition and style.

I went to a wedding recently and I sat next to this really formal guy and I thought “what am I ever going to say to him?” So I asked “Do you cook?” and we were off talking for the rest of the night. He didn’t cook, but his mother was a good cook and his wife was a good cook. So in France, even if they don’t cook, there’s this appreciation for food. There is a tradition—people know—when you say “beurre blanc” people know what it is, even if they don’t make it. It’s a common [cultural] vocabulary, and people know this. Even the avant garde chefs will talk about their childhood food with great love, so everyone remembers grandma making the daube and they’ll make it again with great care—but they’ll also play with it a little bit.

French home cooking is not the scarf; it’s putting the scarf ON the burlap bag. French home dinners are a mix of homemade and store bought (a lot of convenience foods are used), but they’re used stylishly. It’s like deciding “okay, I’ll make the carrot salad, but I’ll buy the carrots grated.” Or “I’ll make the chocolate mousse, but I’ll buy the cookies from someone.”

So it’s an adherence to tradition, with permission to play and be creative.

That’s right. And they have great food magazines in France, so people are constantly getting new ideas, and mixing the old with the new.

What are your go-to recipes in this book?

That’s a tough one. But here are things that I make all the time, over and over again: the salmon rillettes; the gougeres; the onion soup; Michael loves the avocado with pistachio oil; tuna mozzarella pizza; Gerard’s mustard tart; chicken in a pot; hachis parmentier; daube; lamb and apricot tagine; the stuffed pumpkin. Salted butter break-ups; gateau Basque. I love this food.

So do we, Dorie. Thank you so much.

Hachis Parmentier

from Dorie Greenspan’s Around My French Table: More than 300 Recipes from My Home to Yours

Makes 4 generous servings

Many, many years ago, I was lucky enough to have Daniel Boulud, a chef from Lyon who’s made his life in New York City, cook a meal especially for me and my husband. It was luxurious, and at the end of it, after thanking Daniel endlessly, I asked him what he was going to have for dinner. “Hachis Parmentier,” he said with the kind of anticipatory delight usually seen only in children who’ve been told they can have ice cream. We had just had lobster and truffles, but Daniel was about to have the French version of shepherd’s pie, and you could tell that he was going to love it.

Hachis Parmentier is a well-seasoned meat-and-mashed-potato pie that is customarily made with leftovers from a boiled beef dinner, like pot-au-feu. If you have leftover beef and broth from anything you’ve made, go ahead and use it. Or, if you’d like to shortcut the process, make Quick Hachis Parmentier; see Bonne Idée. But if you start from scratch and make your own bouillon, and if you add tasty sausage (not completely traditional), you’ll have the kind of hachis Parmentier that would delight even Daniel Boulud.

You can use chuck, as you would for a stew, but one day my stateside butcher suggested I use cube steak, a cut I’d never cooked with. It’s an inexpensive, thin, tenderized cut (its surface is scored, almost as though it’s been run through a grinder) that cooks quickly and works perfectly here. If you use it, just cut it into 2-inch pieces before boiling it; if you use another type of beef, you should cut it into smaller pieces and you might want to cook it for another 30 minutes.

For the beef and bouillon

1 pound cube steak or boneless beef chuck (see above), cut into small pieces

1 small onion, sliced

1 small carrot, trimmed, peeled, and cut into 1-inch-long pieces

1 small celery stalk, trimmed and cut into 1-inch-long pieces

2 garlic cloves, smashed and peeled

2 parsley sprigs

1 bay leaf

1 teaspoon salt

¼ teaspoon black peppercorns

6 cups water

½ beef bouillon cube (optional)

For the filling

1½ tablespoons olive oil

½ pound sausage, sweet or spicy, removed from casings if necessary

1 teaspoon tomato paste

Salt and freshly ground pepper

For the topping

2 pounds Idaho (russet) potatoes, peeled and quartered

½ cup whole milk

¼ cup heavy cream

3 tablespoons unsalted butter, at room temperature, plus 1 tablespoon butter, cut into bits

Salt and freshly ground pepper

½ cup grated Gruyère, Comté, or Emmenthal

2 tablespoons freshly grated Parmesan (optional)

To make the beef: Put all the ingredients except the bouillon cube in a Dutch oven or soup pot and bring to a boil, skimming off the foam and solids that bubble to the surface. Lower the heat and simmer gently for 1½ hours. The broth will have a mild flavor, and that’s fine for this dish, but if you want to pump it up, you can stir in the half bouillon cube — taste the broth at the midway point and decide.

Drain the meat, reserving the broth. Transfer the meat to a cutting board and discard the vegetables, or if they’ve still got some flavor to spare, hold on to them for the filling. Traditionally hachis Parmentier is vegetableless, but that shouldn’t stop you from salvaging and using the vegetables. Strain the broth. (The beef and bouillon can be made up to 1 day ahead, covered, and refrigerated.)

Using a chef’s knife, chop the beef into tiny pieces. You could do this in a food processor, but the texture of your hachis Parmentier will be more interesting if you chop it by hand, an easy and quick job.

To make the filling: Butter a 2-quart oven-going casserole — a Pyrex deep-dish pie plate is just the right size for this.

Put a large skillet over medium heat and pour in the olive oil. When it’s hot, add the sausage and cook, breaking up the clumps of meat, until the sausage is just pink. Add the chopped beef and tomato paste and stir to mix everything well. Stir in 1 cup of the bouillon and bring to a boil. You want to have just enough bouillon in the pan to moisten the filling and to bubble up gently wherever there’s a little room; if you think you need more (a smidgen more is better than too little), add it now. Season with salt and pepper, especially pepper. If you’ve kept any of the vegetables from the bouillon, cut them into small cubes and stir them into the filling before you put the filling in the casserole. Scrape the filling into the casserole and cover it lightly; set aside while you prepare the potatoes. (You can make the dish to this point up to a few hours ahead; cover the casserole with foil and refrigerate.)

To make the topping: Have ready a potato ricer or food mill (first choices), a masher, or a fork.

Put the potatoes in a large pot of generously salted cold water and bring to a boil. Cook until the potatoes are tender enough to be pierced easily with the tip of a knife, about 20 minutes; drain them well.

Meanwhile, center a rack in the oven and preheat the oven to 400 degrees F. Line a baking sheet with foil or a silicone baking mat (you’ll use it as a drip catcher).

Warm the milk and cream.

Run the potatoes through the ricer or food mill into a bowl, or mash them well. Using a wooden spoon or a sturdy spatula, stir in the milk and cream, then blend in the 3 tablespoons butter. Season to taste with salt and pepper.

Spoon the potatoes over the filling, spreading them evenly and making sure they reach to the edges of the casserole. Sprinkle the grated Gruyère, Comté, or Emmenthal over the top of the pie, dust with the Parmesan (if using), and scatter over the bits of butter. Place the dish on the lined baking sheet.

Bake for 30 minutes, or until the filling is bubbling steadily and the potatoes have developed a golden brown crust (the best part). Serve.

Serving

Bring the hachis Parmentier to the table and spoon out portions there. The dish needs nothing more than a green salad to make it a full and very satisfying meal.

Storing

It’s easy to make this dish in stages: the beef and bouillon can be made up to a day ahead and kept covered in the refrigerator, and the filling can be prepared a few hours ahead and kept covered in the fridge. You can even assemble the entire pie ahead and keep it chilled for a few hours before baking it (directly from the refrigerator if your casserole can stand the temperature change) — of course, you’ll have to bake it a little longer. If you’ve got leftovers, you can reheat them in a 350-degree-F oven.

Bonne idée

Quick Hachis Parmentier. You can make a very good hachis Parmentier using ground beef and store-bought beef broth. Use 1 pound ground beef instead of the steak, and when you add it to the sausage in the skillet, think about adding some finely chopped fresh parsley and maybe a little minced fresh thyme. You can also sauté 1 or 2 minced garlic cloves, split and germ removed, in the olive oil before the sausage goes into the skillet. (The herbs and garlic help mimic the aromatics in the bouillon.) Moisten the filling with the broth, and you’re good to go.